More amazing stuff to know.

Legend has it

Ever wondered how coffee was discovered?

Coffee is believed to have been discovered in Ethiopia in the 9th century, where legend has it that a humble goat herder named Kaldi wandering the lush highlands of Ethiopia, noticed his goats became more energetic after eating the berries of a certain plant. Intrigued, Kaldi decided to sample the berries himself and was amazed by their stimulating effect.

Word of this amazing discovery soon spread throughout the land, and Kaldi found himself sharing his findings with the local monastery. The abbot, curious about the goatherd's claims, decided to brew a drink with the berries and was astounded by the results. The drink kept him alert and focused through the long hours of evening prayer, and soon the entire monastery was buzzing with newfound energy. As news of the energizing berries continued to spread, it eventually reached the Arabian Peninsula and beyond, marking the beginning of a global trade that would shape the world as we know it today.

Thanks to Kaldi's curious mind and the power of the humble coffee bean, we can all enjoy the delicious and invigorating brew that has become a cornerstone of our daily lives.

We explain the supply chain of Ethiopian coffees.

Produced by smallholder farmers.

This delicious Ethiopian coffee is produced by smallholder farmers located around Halo Beriti kebele and nearby villages.

Smallholder farmers plant their coffees often on land parcels as little as 1/8 hectare on average, producing 1.5 to 6 bags of coffee. Talk about making the most of every inch!

After harvest, these smallholders bring their coffee to the local Halo Beriti washing station. That’s where the magic happens. Since the coffee from all these small farms gets mixed together, it’s traceable only to the washing station. The coffee is aggregated, sorted, and then processed at the washing station.

The supply chain of Ethiopian coffees.

Private washing stations

Did you know that about 90% of Ethiopia's coffee comes from smallholder farmers? These hardworking folks deliver their freshly harvested cherries to local, privately owned washing stations. Now, picture this: washing stations are like coffee spas, where the beans either sunbathe on drying beds (for natural-processed coffees) or go through a relaxing wash and dry cycle (for washed coffees).

Many washing station owners also hold an export license, which allows them to sell their coffee directly on the international market—provided they have a contract, of course. Talk about taking their beans global! This particular coffee can be traced back to the Arsosola washing station. So, next time you sip your Ethiopian brew, remember the journey it took from a small farm to your cup. Cheers!

The supply chain of Ethiopian coffees.

Ethiopian Commodity Exchange 'ECX'

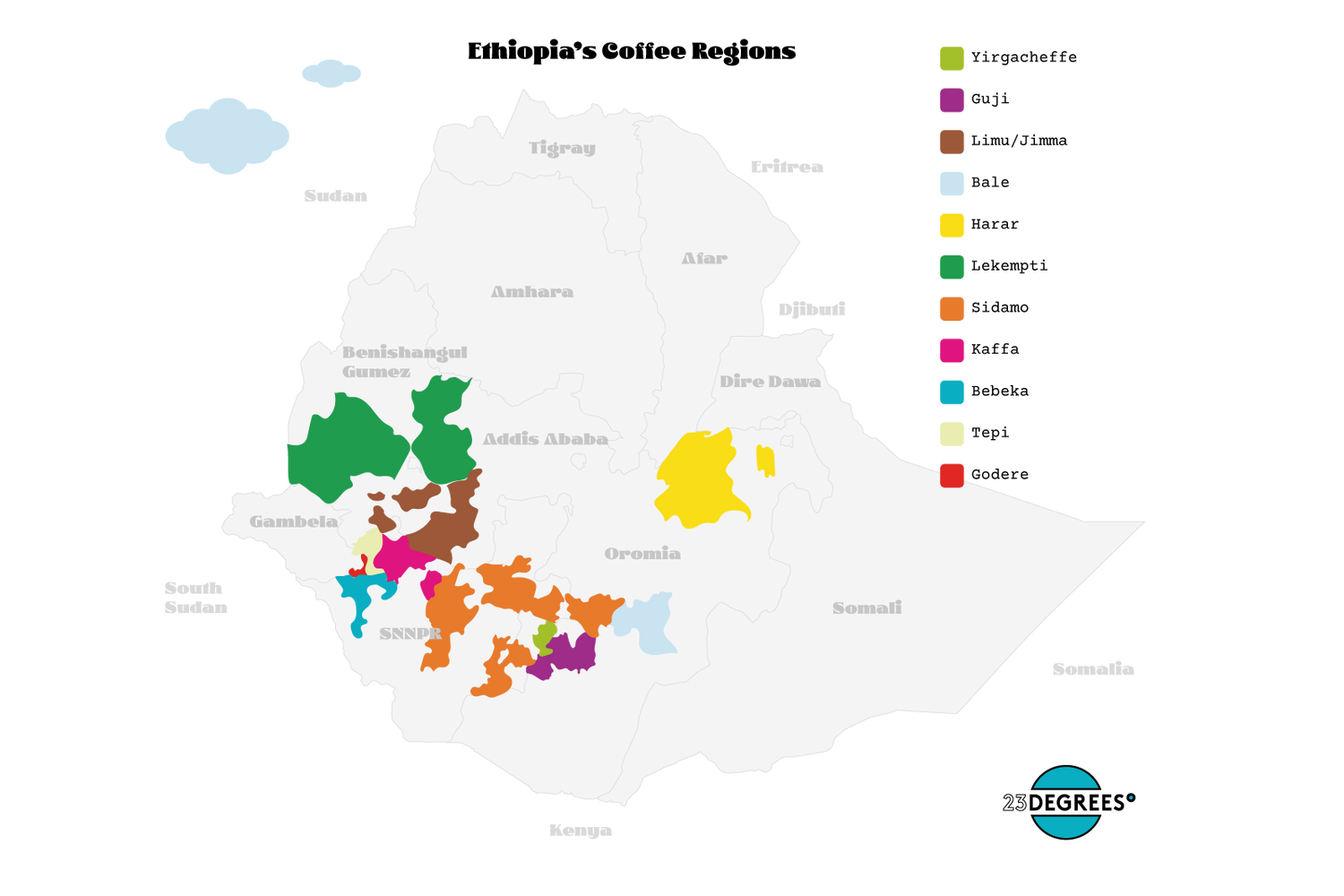

Washing stations without export licenses, or those with unsold coffees even if they do have a license, must sell their coffee through the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) platform. The ECX classifies the coffee based on a basic potential cup score (Q1 for the highest quality, then Q2, Q3, etc.) and location (such as Guji, Yirgacheffe, Harrar, etc.). This classified coffee is then sold to licensed exporters through public daily auctions held in Addis Ababa.

Primary Cooperatives and large farms (over 30 hectares) are allowed to bypass the ECX and export their coffee directly. This system ensures that the best beans find their way to your cup, whether through auction or direct export. So, whether it's from a small washing station or a vast farm, Ethiopian coffee is all about quality and tradition.

The supply chain of Ethiopian coffees.

Dry-mill and exporter

The exporter in Ethiopia typically handles the dry-milling of the coffee, ensuring only the best beans make it to your cup. This process involves removing any unwanted materials like fibers, metals, stones, and sticks. Once the beans are free of debris, they are polished to perfection and sorted by size, density, and colour.

The result? Sorted, uniform coffee beans that are bagged and ready for shipment.

The natural (dry) process explained.

What is a natural processed coffee?

Since coffee beans grow inside a fruit (the coffee cherry), it takes multiple steps to separate the beans from their surrounding fruit flesh after harvest. In the coffee world, we call this the "processing method," and it has a huge effect on what ends up in your cup.

Sun-drying

Once the ripe coffee cherries have been picked, they are spread out to dry in the sun with the fruit flesh left intact around the coffee beans. This allows the beans inside the cherries to soak up all those delicious fruit flavors and sweetness.

Turning

The coffee cherries are regularly raked to ensure even air circulation and consistent drying. The fruit flesh dries around the coffee bean, and this process can take between 10 to 14 days, depending on the local climate, until a moisture level between 10 to 12% is reached.

Hulling

Finally, the coffee beans are "hulled" to remove the dried fruit flesh surrounding them. The beans are now ready to be sorted by size, density, and colour before being bagged and shipped.

It’s a little bit of sunshine and a whole lot of flavour packed into each bean. Enjoy!

About the region: Ethiopia Yirgacheffe

The name "Yirgacheffe" is believed to come from Amharic, one of Ethiopia’s official languages. It’s said to mean “Land of Many Trees” or “Place of Abundant Trees”, and it’s easy to see why. The region is lush, green, and dotted with forest canopy.

In a country with thousands of native coffee varietals, what makes Yirgacheffe so unique? It comes down to the altitude of the mountains in southern Ethiopia, where this coffee is grown. The higher elevation makes growing conditions tougher, but that’s exactly what makes the coffee so special.

At altitude, coffee trees grow more slowly and take longer to mature. This extended ripening period allows the beans more time to develop complex sugars and absorb flavour. It’s no wonder Yirgacheffe is known for producing some of the most iconic coffees Ethiopia has to offer.